We know the Oscar Marzaroli Collection is a great source of inspiration and our guest blogger, Douglas Erskine, uses one of Oscar’s photographs as the starting point for this contribution on Gray Day 2021. Douglas is a researcher and writer with a strong interest in Scottish art. He is currently preparing a monograph on the life and work of the Glasgow artist Alan Fletcher (1930-58).

Of all the images donated to Glasgow Caledonian University by the family of the great Scottish photographer Oscar Marzaroli, few are as striking as the photograph of a young Alasdair Gray posing with his cadaverous alter ego – a portrait by Alan Fletcher – at the 1959 exhibition which Gray organised in his late friend’s memory.

Alasdair Gray, 1959

©Oscar Marzaroli Collection

Fletcher’s spectacularly unnerving investigation into the layers of self which hide behind mere appearance shines a light on the complexity of Gray’s character. Some 70 years after this captivating portrait was painted, as Gray’s seminal novel Lanark turns 40, Scotland and the world have long since caught up with Fletcher’s estimation: Gray’s multifarious body of work – the novels, poems, plays, murals, portraits and prints – mark him out as a complex figure, who remains something of an outlier in the mainstream of Scottish culture. The elaborate nature of Gray’s legacy means that some of his greatest achievements threaten to dwarf his other contributions. The short text which follows, prompted by Marzaroli’s image, comments not so much on the anniversary of Lanark as on Gray’s oft-overlooked practice of promoting and celebrating the work of his talented friends. For me, Gray’s efforts do more than evidence his keen generosity of spirit: rather, I think his promotion of others deserves to be treated as a key aspect of his life’s work.

Alasdair Gray’s support for Alan Fletcher, the extraordinary Glasgow painter and sculptor who exerted an enormous influence on his younger friend, lasted a lifetime.

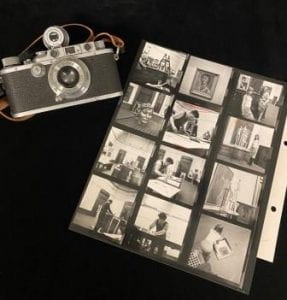

One of Oscar Marzaroli’s cameras and a contact sheet from the hanging of the Alan Fletcher exhibition in 1959

©Oscar Marzaroli Collection

Only days before his death in 2019, Gray remained committed to seeing Fletcher’s work receive the attention it so rightly deserves. In 1959, one year after Fletcher’s tragic death in an accident in Milan, Gray, along with Fletcher’s close friends Douglas Abercrombie, Carole Gibbons and the sculptor Benno Schotz, staged a large-scale memorial show of the artist’s work in Glasgow’s McLellan Galleries. Although Fletcher never received proper recognition in his lifetime, even within Glasgow, the surprising power of his dark, avant-garde imagery, coupled with the commendable efforts of his closest friends, ensured the exhibition was roundly praised: around a thousand visitors saw the show during its short run and the publicity provided by the BBC’s arts review excited interest in Fletcher’s work from a range of dealers. Sales to private collectors and public bodies were good: the Arts Council bought three works, and the Hunterian Art Gallery two, with the takings going towards the erection of Fletcher’s gravestone in Milan. The efforts of Abercrombie, Gibbons and Gray – who insisted that almost all of Fletcher’s works were shown – were invaluable in stoking the flame of Fletcher’s memory, and the 1959 Memorial Exhibition forms a baseline for any assessment of the artist’s work. Gray’s commitment to his friend’s memory in the years after the exhibition took many forms: he donated work by Fletcher to the National Galleries, Glasgow City Council, Strathclyde University and the Hunterian Art Gallery; he encouraged collectors and dealers to buy work; and he wrote on Fletcher quite extensively, devoting an entire chapter to the artist in his 2010 book A Life in Pictures, which is essential reading for anyone eager to learn more about the man and his art.

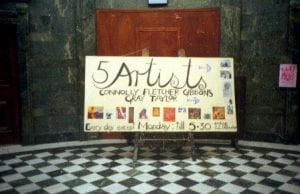

Gray included Alan Fletcher’s work in an ambitious group show staged in 1986, alongside his own work and that of John Connolly, Carole Gibbons and Alasdair Taylor. Organised in response to the excitement surrounding the “New Glasgow Boys” who emerged from the Glasgow School of Art in the 1980s, the Five Artists exhibition drew attention to the work of a group of older artists who had been all but ignored in Scotland.

Handmade sign by Alasdair Gray to publicise the Five Artists show (McLellan Galleries, 1986), with small reproductions of work by John Connolly, Alan Fletcher, Carole Gibbons, Alasdair Gray and Alasdair Taylor – photograph ©Richard Demarco

Their styles were remarkably diverse: Connolly submitted a number of serene portrait heads and ingeniously abstracted sculptures in steel and wood; Gibbons took possession of her space with a large number of absorbing, intensely coloured canvases; Taylor’s output was represented by freely painted abstracts, experimental sculptures and evocative “mood paintings”. The fact that Gray was now a celebrated writer, following the publication of Lanark in 1981, helped to publicise the show and, in the eyes of the public, conferred a certain esteem onto the artists he introduced. But stumbling blocks were many: most importantly, the Five Artists show was an incredibly expensive venture which the Arts Council were unwilling to support. It is a mark of Gray’s generosity and respect for Connolly, Fletcher, Gibbons and Taylor that, in order to fund the exhibition, he sold a trove of very intimate diaries to the National Library of Scotland. Although no English gallery was prepared to work with Gray, he was heartened to receive support in Scotland: Duncan Macmillan at the Talbot Rice and Andrew Brown at the 369 Gallery showed the exhibition in Edinburgh before it toured to Aberdeen Art Gallery, where it was accommodated by Ian McKenzie Smith. Gray might have been left out of pocket by the end of the run, but in organising and administrating an impressive show, and in producing a richly illustrated set of catalogues which could be pored over long after the exhibition ended, he had successfully introduced the work of the five artists to a new generation who were hungry for art.

Although Alasdair Gray’s support for John Connolly and Carole Gibbons, as well as Alan Fletcher, should not be understated by any means, it is worthwhile drawing attention to the especially close relationship he shared with Alasdair Taylor. The pair had taken part in a number of two-man shows, largely out of necessity, from the early 1960s onwards and as Gray’s profile swelled he was sure to help his friend into the limelight: the fact that he and Taylor shared a show as recently as 2009, when Gray could easily have staged an impressive exhibition of his own work alone (and enjoyed all the attention himself!), demonstrates his lasting commitment to his friend and his work. Of course, it is not a question of Taylor hanging onto Gray’s coattails: he, like all of the artists mentioned in this text, had exhibited widely and sold a great deal of work without the benefit of Gray’s support. Moreover, a critical analysis of Taylor’s work, which Gray included in his 1985 book Lean Tales, leaves the reader in no doubt as to the artist’s talent. Gray continued to honour his friend’s legacy after Taylor’s death in 2007: he continued to write about Taylor’s work; he secured a large government grant which paid for Taylor’s output to be professionally catalogued; and, shortly before his own death in 2019, in spite of ill health and reduced mobility, Gray was excited to visit an exhibition of Taylor’s work which was to be staged in 2020 by the artist’s family. Gray’s great generosity was much appreciated by the artist’s family, by Taylor himself, and by the countless admirers who discovered his work through Gray’s efforts.

In drawing attention to just a few examples, I hope this short text has gone some way towards suggesting the breadth and value of the support which Alasdair Gray was keen to provide for his fellow artists over the course of his career. Gray’s dedication to promotion remained a constant throughout his mature life: the efforts of the younger man who appears in Marzaroli’s image were as sincere as those of the older man – who, just a few days before his death, was delighted to rediscover that same image, which he pasted into one of the final entries in his diary. In spite of Gray’s sincerity, the success of some of his ventures might be open to question and unfortunately, it must be said that none of the artists listed above have yet had their due. But Gray’s efforts did a very great deal to shed light on the work of these overlooked figures. I maintain that his efforts have not yet been fully appreciated. Gray’s promotional practice has been reduced largely to anecdotes passed among friends, whereas it deserves to be regarded as a central aspect of his life’s work.

Gray’s eagerness to honour the lives and efforts of others is braided throughout his body of work: indeed, it might be that which unites much of his output. This concern does a great deal to root his work in a specific time and place and often reinforces a delicious realism which is surely part of his work’s lasting appeal. With Lanark, for instance, the brilliance of Gray’s innovation – his decision to base almost all of the characters within his great work on real people, to a greater or lesser extent – remains undimmed after 40 years. Anybody who wishes to appreciate, in full, this key concern must not neglect Gray’s efforts to celebrate his friends and their work, not just in fiction – or through fiction – but in actuality.

In capturing the young Alasdair Gray taking a break from hanging the walls of the McLellan Galleries with Alan Fletcher’s inspired but overlooked work, Oscar Marzaroli has created an important document which, like Fletcher’s portrait of Gray, helps us to understand something more of this remarkable man.

**We are currently fundraising to catalogue and digitise the Marzaroli Collection. Find out more here.

Note on references – In preparing this text, I consulted two of the very best books on Alasdair Gray’s work: A Life in Pictures by Alasdair Gray (published by Canongate in 2010) and Alasdair Gray: A Secretary’s Biography by Rodge Glass (Bloomsbury, 2009). I also used information gleaned from personal correspondence, private archives and material from my own collection. I would be very happy to provide a full list of references to anyone who might wish to get in touch – they can do so via Carole McCallum at GCU.